Magnesium supplementation in sports: where is the evidence?

The nutritional supplement market today is flooded by a wide diversity of magnesium supplements. The sales of magnesium supplements is also promoted by attractive claims such as ‘improves muscle contraction’, ‘stimulates energy production’, ‘reduces fatigue’, ‘increases mental alertness’, and last but not least ‘prevents muscle cramps’. Not to talk about the ultimate claim: performance enhancement! But what is the scientific evidence to support the use of magnesium supplements in the context of exercise and sports performance in healthy individuals?

Magnesium is a pivotal mineral in human health and functional capacity.

Magnesium plays an important role in a wide range of physiological and biochemical processes in the human body. Magnesium amongst others is crucial for muscle contraction and nerve function, muscular energy production and anabolism, bone synthesis and repair, as well as gene expression by regulation of DNA and RNA synthesis. Given the pivotal role of magnesium in human physiological regulation, whole body magnesium balance is tightly regulated by both intestinal magnesium absorption and via urinary magnesium excretion. As a result, magnesium deficiency due to low dietary intakes is most uncommon in healthy populations. Nonetheless, excessive magnesium losses due to disease states, alcoholism, intake of certain medication, or intake of excess zinc supplements, can lead to magnesium deficiency, indeed. Early symptoms of deficiency are loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and general fatigue and weakness. In such cases oral magnesium supplementation is obviously recommended.

What is the need for dietary magnesium intake in fit and healthy individuals?

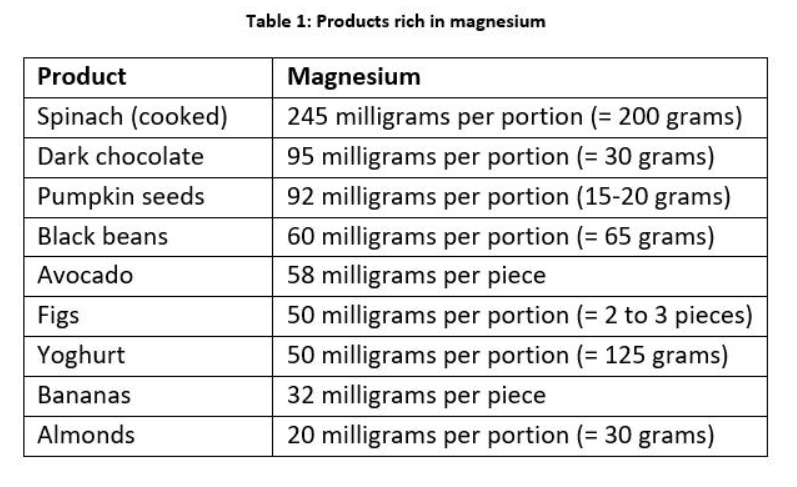

The total magnesium content in the human body is about 20-30 grams, the bulk of which is located inside the cells. About 50% of whole body magnesium is integrated in bones, whilst the other half is mostly contained in skeletal muscles and soft tissues. Blood magnesium content accounts for less than 1% of the whole body magnesium store. Surprisingly, assay of red blood cell magnesium level is becoming increasingly popular as a so-called preventive strategy to assess magnesium status in athletic populations. But various cell types handle magnesium quite differently, which makes erythrocyte magnesium content to be an inadequate reference to assess the need for magnesium supplementation in healthy individuals. Depending on the reference values used, recommended dietary allowance for magnesium is about 300-350 mg per day for women, versus 350-400 mg per day for males, which represents ~1% of the total body magnesium pool. Given that magnesium is widely distributed in foods from both plant and animal sources, as well as in commercial waters and most fruit juices, maintenance of magnesium balance by routine dietary intake is not a difficult challenge in healthy individuals. Dark-green leafy vegetables, legumes, nuts and whole grains or fiber-rich foods all are excellent sources of magnesium (see Table 1). Nonetheless, it is important to note that not all of the dietary magnesium ingested is absorbed. The lower the magnesium status in the body, the more of this element is absorbed in the gut. Also the kidneys are crucial in magnesium homeostasis as serum magnesium concentration is primarily controlled by its excretion in urine. Under normal physiological conditions no more than ∼100 mg of magnesium per day is excreted via urine. A normal cup of cereals completed with some nuts and seeds at breakfast largely compensates for such low daily excretion rate.

But what is the impact of strenuous exercise on magnesium balance, and is there a role for magnesium supplements in exercise management?

But what is the impact of strenuous exercise on magnesium balance, and is there a role for magnesium supplements in exercise management?

But what is the impact of strenuous exercise on magnesium balance, and is there a role for magnesium supplements in exercise management? Exercise and training in healthy individuals does not cause magnesium deficiency.

A traditional argument raised to promote the sales of magnesium supplements in fit individuals is that magnesium losses via sweating produce a negative whole body magnesium balance. However, contrary to sodium, sweat magnesium concentration is very low, and even in heavy sweaters only small amount of magnesium are excreted. As a matter of example: in one study healthy volunteers cycled for ~8 hours in 37°C. Total magnesium loss was no more than 15-20mg for the full performance, which corresponds to the amount of magnesium supplied by half a banana or a small cup of milk. Clearly, the standard ingredients of a well-balanced sports diet easily compensate for sweat magnesium losses during exercise. Evidence to indicate that exercise and training can cause magnesium deficiency to a degree that may impact either health or exercise performance is lacking.

Magnesium supplementation does not prevent exercise-induced muscle cramps.

Another common argument used to promote magnesium supplementation in physically active or athletic populations is that exercise-induced muscle cramps are caused by magnesium deficiency. However, such mechanism is contradicted by the scientific data available today. Muscle cramps during rest or sleep in pathological conditions associated with explicit magnesium deficiency can be treated by short-term magnesium supplementation, indeed. But the physiological mechanisms underlying exercise-associated muscle cramps are very different from the above. Scientific evidence indicates that deficient fluid and sodium balance, alone or in conjunction with neuromuscular disturbances directly cause muscle cramping during exercise. Clearly, the incidence of muscle cramps is much higher during exercise-induced dehydration in the heat than in colder conditions, and is also higher during very prolonged exercise causing neuromuscular fatigue. For sure, acute magnesium supplementation before exercise is entirely ineffective to prevent muscle cramping during exercise because intracellular magnesium balance reflects the long-term homeostatic balance between magnesium intake and excretion.

Conclusion

Literature data taken together does not provide evidence to support the use of magnesium supplements to stimulate either health or performance in athletic populations or in individuals involved in strenuous exercise.

Take home message

- Magnesium plays an important role in physiological adaptation to exercise and training.

- A well-balanced diet including dark-green leafy vegetables, legumes, nuts, whole grains, fiber-rich foods, fruit juices and dairy products supplies ample amounts of magnesium to maintain magnesium homeostasis even in athletic populations.

- Magnesium losses via sweating are minor and are very easily compensated for by the use of magnesium-rich foods.

- Magnesium supplementation does not prevent exercise-associated muscle cramps.

- Evidence to support either acute, short-term, or long-term magnesium supplementation in sports is lacking.

References

- Troy, D.C., Kenefick, R.W., Cheuvront S.N., Lukaski, H.C., Sawka, M.N. (2008). Effect of heat acclimation on sweat minerals. Med Sci Sports Exerc. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18408609/.

- Consolazio, C.F., Matoush, LR.O., Neslon, R.A., Harding, R.S., Canham, J.E. (1963). Excretion of sodium, Potassium, Magnesium and Iron in Human Sweat and the Relation of Each to Balance and Requirements. The American Society for Nutrition. https://academic.oup.com/jn/article-abstract/79/4/407/4779263?redirectedFrom=fulltext/.

- Nielsen, F.H., Lukaski H. (2006). Update on the relationship between magnesium and exercise. International Society for the Development of Research on Magnesium 19(3), 180-9. http://www.jle.com/download/mrh-272229-update_on_the_relationship_between_magnesium_and_exercise--WoKmfX8AAQEAAExMKR8AAAAI-a.pdf.

- Miller K.C., Huxel, K.C. (2010). Exercise-associated muscle cramps: causes, treatment and prevention. Sport Health, 279-283. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3445088/

- Scott, R.G., Allen G.M. Sekhon, R.K., Musini V.M., Khan, K.M. (2012). Magnesium for skeletal muscle cramps. Cochrane library. href="https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009402.pub2/full">https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009402.pub2/full

- Newhouse, I.J., Finstad, E.W. (2000). The effects of magnesium supplementation on exercise performance. Clin J Sport Med, 195-200. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10959930/

- Lukaksi, H.C. (2000). Magnesium, zinc, and chromium nutriture and physical activity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 585s-593s. , https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/72/2/585S/4729660